Review Article

Wildlife Zoonoses

David T. S. Hayman*

Cambridge Infectious Diseases Consortium, Department of Veterinary Medicine, University of Cambridge, Madingley Road, Cambridge, CB3 0ES, UK

Department of Biology, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado, CO80523, USA

Animal Health and Veterinary Laboratories Agency, Wildlife Zoonoses and Vector-borne Diseases Research Group, Department of Virology, Veterinary Laboratories Agency – Weybridge, Woodham Lane, Weybridge, New Haw, Addlestone, Surrey, KT15 3NB, UK

- *Corresponding Author:

- David T. S. Hayman

Department of Biology

Colorado State University, Fort Collins

Colorado, CO80523, USA

E-mail: dtsh2@cam.ac.uk

Received date: October 05, 2011; Accepted date: December 08, 2011; Published date: December 20, 2011

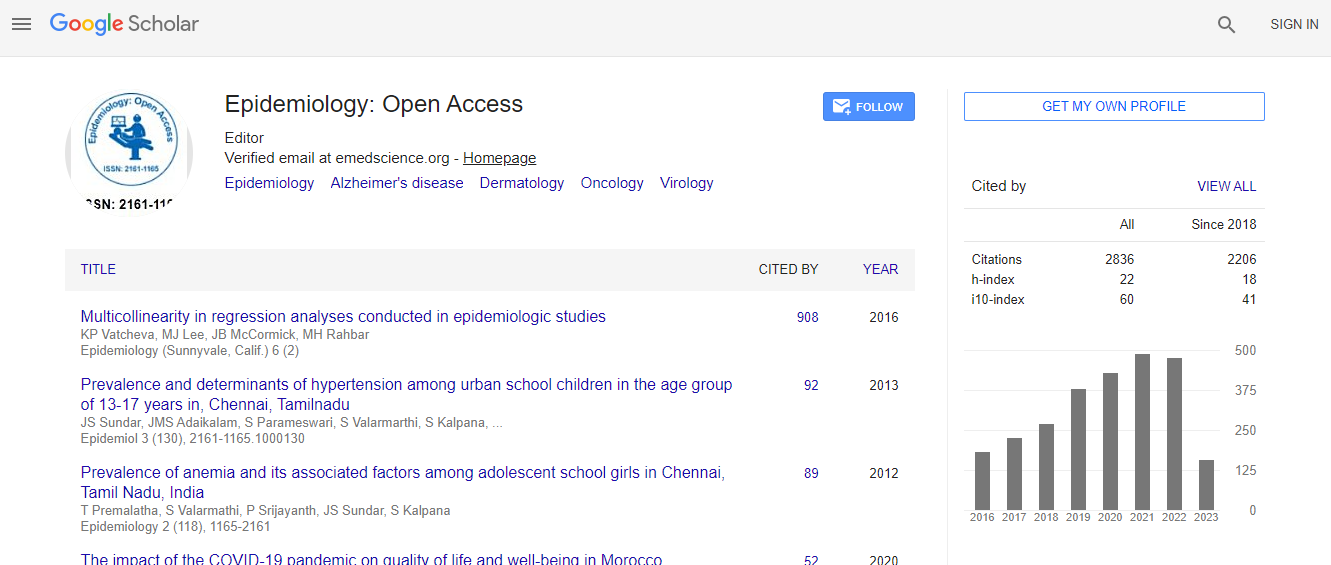

Citation: Hayman DTS (2011) Wildlife Zoonoses. Epidemiol S2:001. doi:10.4172/2161-1165.S2-001

Copyright: © 2011 Hayman DTS. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Infectious diseases are still to be found among the top causes of human deaths globally. The majority of human pathogens are and many have their origins in wildlife. The cost of new infections to societies in terms of human mortality and morbidity can be enormous. Humans have contact with vastly more infectious agents of wildlife origin than spillover and emerge in human populations. Therefore, understanding and predicting zoonotic infection emergence is complex. Changes in the ecology of the host(s), the infection or both, are thought to drive the infection emergence in a range of different host-infection systems. Here key recent studies regarding how changes in host ecology, receptor use and infection adaptation relate to spillover and emergence from wildlife reservoirs are reviewed. The challenges wildlife zoonoses pose to epidemiologists are also discussed, along with how developments in technology, such as PCR, have changed perspectives relating to wildlife as hosts of zoonotic infections.