Review Article

Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO)

Ahmed Salem* and Bani Chander RolandDepartment of Gastroenterology, Johns Hopkins university, USA

- *Corresponding Author:

- Ahmed Salem

Johns Hopkins University

Gastroenterology 601 N Wolf Street Baltimore

Maryland, USA

Tel: 4107332204

E-mail: Asalem10@jhmi.edu

Received date: September 02, 2014; Accepted date: October 06, 2014; Published date: October 11, 2014

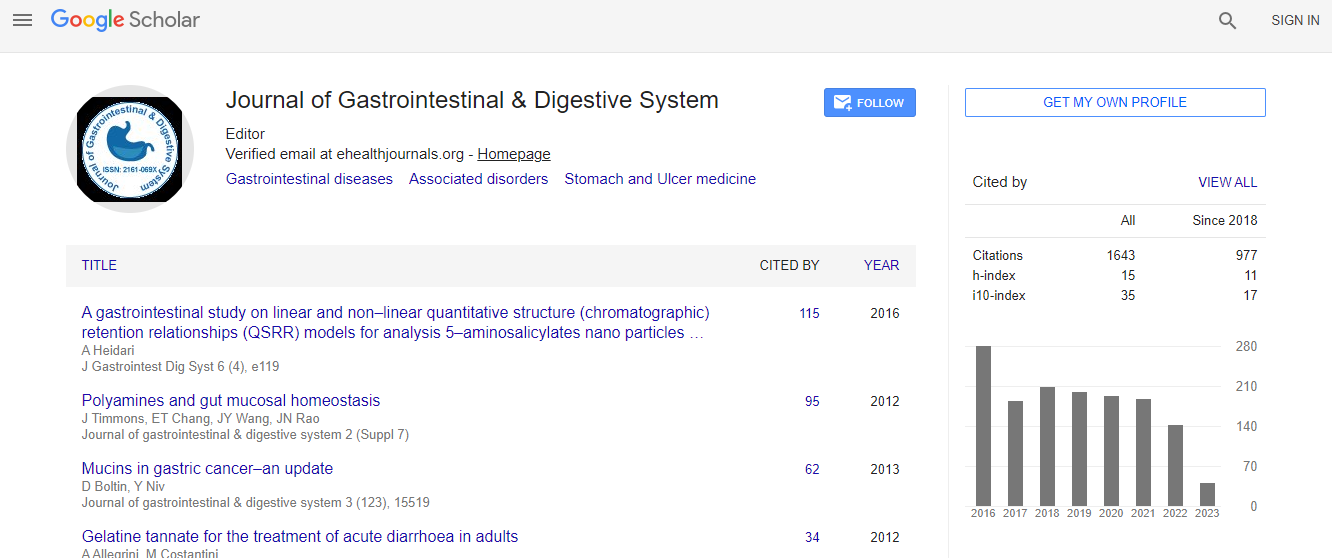

Citation: Salem A, Roland BC (2014) Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO). J Gastroint Dig Syst 4:225. doi: 10.4172/2161-069X.1000225

Copyright: © 2014 Salem A, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

In the healthy human being, there are a variety of intrinsic defense mechanisms that control the number of bacteria and its composition in various parts of the . These defense mechanism include gastric acid secretion, preserved gastrointestinal motility (particularly phase III of the migrating motor complex), normal bacterial microflora, pancreatic biliary secretion, and an intact ileocecal valve, all of which protect against bacterial overgrowth. Any disturbance or alteration in the inherent defense mechanisms can lead to small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO); therefore, we can define SIBO as an increase in the number and/or an alteration in the type of bacteria found in the small bowel. The etiology of SIBO is presumably multiefactorial and complex, including alternation of gastric acid secretion (primarily in the form of achlorhydria and pancreatic and biliary secretions insufficiency), chronic disease (e.g.renal failure, liver cirrhosis) and old age are among some of the different causes that result in competition between the host and overgrown bacteria for the ingested nutrients and catabolism of these nutrients which subsequently lead to release of toxic metabolites causing variable degree of injury to the proximal intestinal cells. The clinical features of SIBO are widely variable, including abdominal bloating, nausea, abdominal pain, chronic diarrhea, flatulence and weight loss; however, some patients have only subtle symptoms. For this reason, the diagnosis may often be overlooked. Although the diagnosis of SIBO is complex;, there are a few different approaches that may be used to help establish the diagnosis in patients with suspected SIBO. The gold standard for diagnosis remains microbial investigation of jejunal aspirate. Non-invasive, indirect methods include hydrogen and methane breath testing (using either glucose or lactulose as a substrate). A third approach is the empiric treatment in patients with suspected SIBO with a trial of antibiotics with subsequent evaluation of symptomatic response and normalization of breath testing. The underlying principles of treatment of SIBO are complex and typically treated with a course of antibiotics as first line therapy along with addressing the underlying defect. Additionally, probiotics, herbals, and certain diets may also play a significant role in the treatment of SIBO in the future.